What is hypothesis?

Hypothesis is family of testing libraries which let you write tests parametrized by a source of examples. A Hypothesis implementation then generates simple and comprehensible examples that make your tests fail. This simplifies writing your tests and makes them more powerful at the same time, by letting software automate the boring bits and do them to a higher standard than a human would, freeing you to focus on the higher level test logic.

It is in short THE testing tool. As quoted by the author, “The purpose of hypothesis is to drag the world kicking and screaming into a new and terrifying age of high quality software”

How to use hypothesis?

Hypothesis integrates into your normal testing workflow. Getting started is as simple as installing a library and writing some code using it - no new services to run, no new test runners to learn.

We can install it by,

pip install hypothesis

The main thing about hypothesis is Strategy. A strategy is a recipe for describing the sort of data you want to generate. Rather than having to hand-write generators for the data needed, we can just compose the ones hypothesis provides us with, to get the data in the required format

Ex: If we need a list of floats which are definitely a number and not infinite, we can use the strategy

lists(floats(allow_nan=False, allow_infinity=False))

As well as it is easier to write, the resultant data will ususally have a distribution that is much better at finding edge cases than most of the heavily tuned maual implementations

Once we understand data generation for tests, the main entrypoint to Hypothesis is the @given decorator. It takes a function with some arguments as input & turns it into a normal test function.

This helps us to realize that hypothesis is not itself a test runner, but it runs alongside our testing framework and all it does is to expose a function of the appropriate name which the test runner picks up.

A simple example illustrating @given decorator (taken from hypothesis docs),

from hypothesis import given

from hypothesis.strategies import text

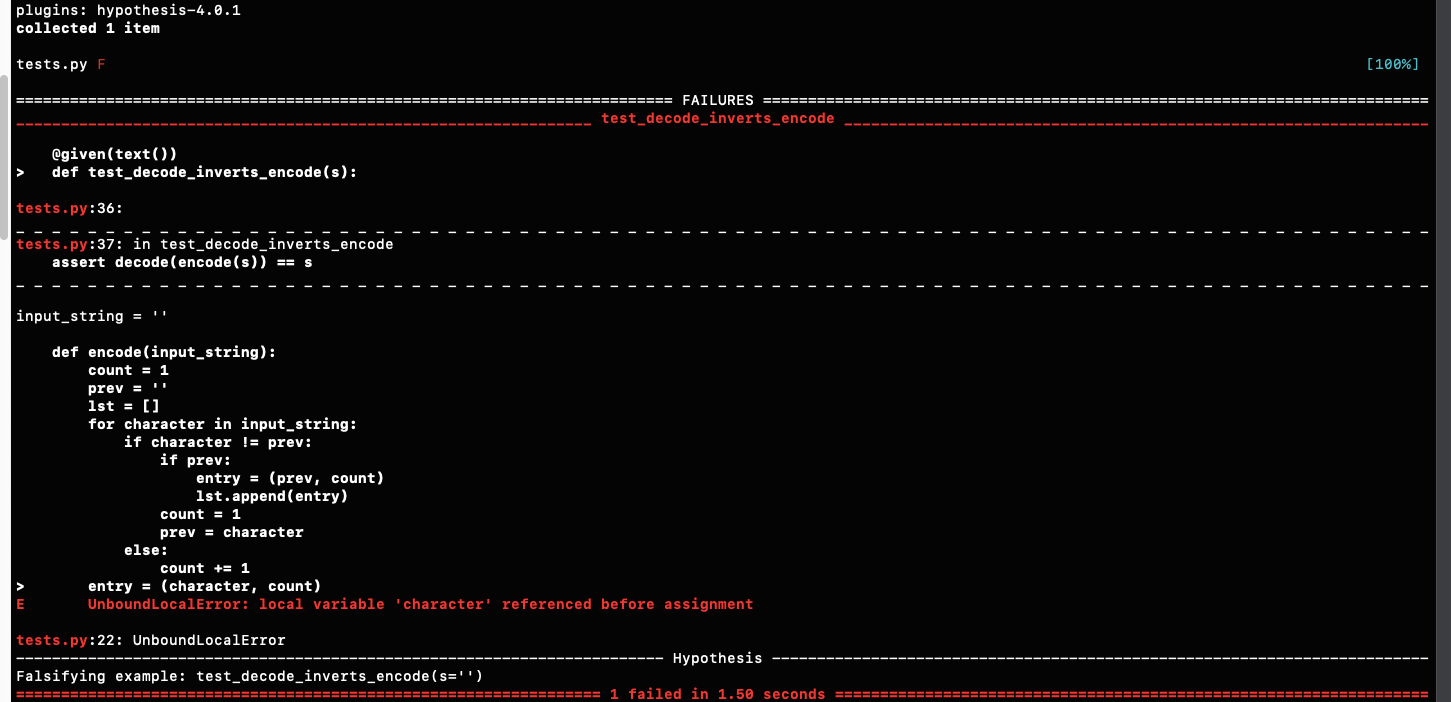

def encode(input_string):

count = 1

prev = ''

lst = []

for character in input_string:

if character != prev:

if prev:

entry = (prev, count)

lst.append(entry)

count = 1

prev = character

else:

count += 1

entry = (character, count)

lst.append(entry)

return lst

def decode(lst):

q = ''

for character, count in lst:

q += character * count

return q

@given(text())

def test_decode_inverts_encode(s):

assert decode(encode(s)) == s

In the function above we are trying to encode something and then decode it to get the same value back. We find a bug immediately,

Hypothesis correctly points out that this code is simply wrong if called on an empty string.

If we wanted to make sure this example was always checked we could add it in explicitly by using the @example decorator i.e.

@given(text())

@example('')

def test_decode_inverts_encode(s):

assert decode(encode(s)) == s

This ensures to show what kinds of inputs are valid or to ensure that particular edge cases such as "" are tested everytime.

Note that both @example and @given support keyword arguments as well as positional i.e.

@given(s=text())

@example(s='')

def test_decode_inverts_encode(s):

assert decode(encode(s)) == s

Once hypothesis finds an error with respect to a test after multiple test runs, it will continue to fail with the same example everytime. This is because Hypothesis has a local test database where it saves all the examples which failed. When we rerun the test, it will first try the previous failure. This is important because, even if at heart hypothesis is random testing, it is repeatable random testing, i.e. a bug will never go away by chance, because further tests will run only, if the previous failure no longer failed.

Using Hypothesis with Django Rest Framework

Now, taking the above example as a sample, lets test it out on a DRF Application. I’ll be using my previous Polls API clone from https://github.com/yvsssantosh/django-polls-rest

Navigate to the file tests.py in polls directory, and lets understand the file part by part.

# Default imports

import time

from hypothesis import given, settings, strategies as st

from django.contrib.auth.models import User

from hypothesis.extra.django import TestCase, from_model

from rest_framework.test import APIClient, APIRequestFactory

# Custom imports

from polls import apiviews

# Our testing class

class TestPoll(TestCase):

# Initial setup

def setUp(self):

self.client = APIClient()

self.factory = APIRequestFactory()

self.view = apiviews.PollViewSet.as_view({"get": "list"})

self.uri = "/polls/"

# Testing create polls

@settings(deadline=2000, max_examples=10)

@given(from_model(User))

def test_create(self, user):

user = self.set_password_to_user(user)

self.client.login(username=user.username, password="hello")

body = {"question": st.text(), "created_by": user.id}

time.sleep(1)

response = self.client.post(self.uri, body)

self.assertEqual(

response.status_code,

201,

"Expected Response Code 201, received {0} instead.".format(

response.status_code

),

)

# Testing list polls - Method I

@settings(deadline=2000, max_examples=10)

@given(from_model(User))

def test_list(self, user):

request = self.factory.get(self.uri)

request.user = user

response = self.view(request)

self.assertEqual(

response.status_code,

200,

"Expected Response Code 200, received {0} instead.".format(

response.status_code

),

)

# Testing list polls - Method II

@settings(deadline=2000, max_examples=10)

@given(from_model(User))

def test_list2(self, user):

user = self.set_password_to_user(user)

self.client.login(username=user.username, password="test")

response = self.client.get(self.uri)

self.assertEqual(

response.status_code,

200,

"Expected Response Code 200, received {0} instead.".format(

response.status_code

),

)

# Just a method to set password

def set_password_to_user(self, user):

user.set_password("hello")

user.save()

return user

- The first few lines indicate basic imports which are required for tests. The major imports being,

from hypothesis import given, settings

from hypothesis.extra.django import TestCase, from_model

@given decorator is used because it is the entry point for hypothesis testing

@settings decorator is used to modify the way tests are to be implmeneted. More on this will be explained below.

We will be importing from TestCase from hypothesis, as it helps all the decorators to work, according to our methods

from_model is used to generate random data according to the given model

-

Custom imports include importing API views. Then we define our class

TestPoll(Note that we are inheriting fromhypothesis.django.extra.TestCase). After this we have the initial setup which sets up APIRequestFactory, APIClient which are helpful in making requests, and authenticating the user respectively. -

Once we are done with initial setup, we explore the main part where we’re gonna test our application. The major advantage with hypothesis is that, with just a few decorators, we can simplify our tests which improves readibility as well as thoroughness of our tests.

@settings(deadline=2000, max_examples=10)

@given(from_model(User))

def test_create(self, user):

user = self.set_password_to_user(user)

self.client.login(username=user.username, password="hello")

body = {"question": st.text(), "created_by": user.id}

response = self.client.post(self.uri, body)

self.assertEqual(

response.status_code,

201,

"Expected Response Code 201, received {0} instead.".format(

response.status_code

),

)

-

A

deadlineis the timeframe (in ms), for max which the test is allowed to run. Default value is200ms. But with that default value, our tests threw an errorDeadlineExceeded. We can test it by removing that parameter in the@settingsdecorator. -

max_examplesis used to define the number of iterations we want to test our application randomly. In our case, the test is run with 10 different random test cases. This is all done with the help of@givendecorator andfrom_modelmethod. -

The

from_modelmethod is really helpful to generate random data with respect to a model. For example, if we want to generate a random instance ofUsermodel, we’d just have to do add it to the given decorator, and expect it as a paramater in the following method. -

Note that in the response body, for question parameter, we are passing

st.text()which again, randomly generates a string and then the request is posted.

We can test our application the way we used to, i.e.,

python manage.py test

Ultimately hypothesis provides readability, repeatability, reporting and simplification for randomized tests, and it provides a large library of generators to make it easier to write them. It is also really helpful in generating random use cases which even the human mind can’t think of sometimes.

Thank you for reading the Agiliq blog. This article was written by yvsssantosh on Jan 19, 2019 in python , django , hypothesis , testing , django rest framework , drf , polls api .

You can subscribe ⚛ to our blog.

We love building amazing apps for web and mobile for our clients. If you are looking for development help, contact us today ✉.

Would you like to download 10+ free Django and Python books? Get them here